CNN has recently posted a very interesting article about psychoanalysis in Argentina and how it is thriving there. If you would like to see the article follow this link:http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/28/health/argentina-psychology-therapists/index.html. A very interesting cultural difference in attitudes to the analytic therapies.

Author: Melonie Bell

On the Derivation of the Word Therapist

Charles Ashbach, Ph.D., therapist in the Philadelphia area.

Faculty of the International Psychotherapy Institute (IPI)

Faculty of the Philadelphia Psychotherapy Study Center (PPSC).

E-Mail: cashbach1@verizon.net.

The training for psychotherapy by and large focuses, as it should, on the development of capacities within the therapist that enable him or her to make contact with the emotional and psychic-unconscious dimensions of the self and through this “self development” comes the capacity to be able to tune in and detect the unconscious of the patient’s mind, self and personality. The development of empathy, intuition, patience, perspective, context, symbolism and the negative capability are all emphasized in helping a person prepare for the rewarding, though incredibly demanding profession of psychotherapist. I want to share some thoughts I’ve come by in the study of our most demanding profession.

For some years I have been a member of a group of colleagues who have been studying the primitive dimensions of the human personality. Not only through various schools and approaches within psychoanalytic psychology but also through myth, anthropology, sociology and the history of religion. During that time I was fortunate to come upon the origin of the word therapist. This occurred when a colleague of mine commented on a seminar he had attended and how the presenter made mention of the root of the English word therapist being the Greek word Therapon. My colleague said it had to do with the master-slave relationship between a royal and his servant.

I was struck by this idea and my research revealed the Greek word Therapon described an individual whose job or role was to be an attendant, companion of lower rank, aide, minister, slave, servant or replacement committed to the willing sacrifice for a human master or supernatural deity. It was used in the Old Testament to describe Moses’ relationship to his god, and was understood as “servant” of god. I was especially impressed by the “sacrificial” aspect of the term when understood as “slave,” “servant” or “replacement.” Further research revealed the use of the Therapon in Homer’s Iliad regarding the role of Patroclus.

In the Iliad, Patroclus, Therapon to mighty Achilles, takes up Achilles’ cause when he (Achilles) peevishly withdraws from the battle against the Trojans after an argument with King Agamemnon. In that dispute Agamemnon demanded a certain public deference from Achilles as well as demanding that Achilles give up his beautiful female slave to Agamemnon. Patroclus, recognizing the de-moralizing threat of Achilles’ withdrawal, put on his master’s majestic armor and went out onto the field of battle to fight the mighty Trojan warrior, Hector. Patroclus sought to save the day for Greece and to save Achilles’ sacred name. Of course he did neither. Hector immediately killed Patroclus and his death spurred the mighty Achilles to take us his weapons and defeat the Trojan army and drive them back behind the Walls of the city.

The point here is that the Therapon is prepared to sacrifice his, or her, life for the good of the master. The implication being, that at the core of the human unconscious is a sacrificial component, an archetype if you will, that motivates an individual to take up a particular form of subjugation and sacrifice as their life’s work. This seemed to be very important to reflect upon.

Heinrich Racker in his brilliant treatise on the role of the therapist, Transference and Countertransference (1968) writes compellingly about the unconscious need at the core of the therapist’s personality to rescue his or her own internal damaged objects. He says we become therapists to repair and restore these precious objects in order to free ourselves from the responsibility and guilt of having let them down or aggressed against them. Ultimately, Racker believes, that our metabolization of this guilt provides the path to become a competent, caring and realistic professional, empowered but limited, motivated but not manically so. As Freud says that we must be careful not to seek cure at any price. The goal of therapy, Freud says, is to offer the patient the awareness of choices and then ultimately to stand back so he or she can make the choices that define their life.

Racker seeks to remind us that it is the encounter with our unconscious that prepares us for the encounter with the patient’s. It is our ability to acknowledge our limits and our vulnerabilities, our terrors and our dreams, that help us to offer this form of integration and humility to our patients.

In the work with the most difficult and demanding group of patients, those that occupy the class that Freud (1923) described as manifesting the “negative therapeutic reaction” (NTR), we frequently encounter the collision of our therapeutic self with the split self of the patient. The patient’s self is split due to the operation of traumatic components that have driven that individual to both desperately seek help and simultaneously to resist help and the dreaded dangers of change and transformation. We realize after some time and a great amount of suffering that the collision between these two aspects of the patient’s self means a great challenge to our therapeutic self.

With such patient’s there is a desperate need to see the self as “innocent” and the “victim” of circumstances. These needs clash with their unconscious dimension of self-awareness that perceives the aggression and conflict that flows and has flowed from their self toward their objects. This battle between their love and hate, that is their primordial ambivalence, is complicated by the attack of the super-ego that holds them in a dreadful state of moral judgment and condemnation. Melanie Klein (1935) defines this moment as the crisis of the “depressive position.” Often their only recourse is to projectively identify their dilemma into and onto the therapist and ask us to take their place on the sacrificial altar of their relentless self-judgment, punishment and guilt.

Here the battle between empathy and enmeshment is most acutely engaged. The patient frequently feels that “if we loved them” we would take their place in their struggle with their bad-object conscience. Other times they identify with the bad object and seek to have us offer up ourselves so that they may remain free and clear of any responsibility for the injuries to their love-objects. In either the depressive or the paranoid version of the request, the patient is asking us to become the “scapegoat” for them. It is here that we must be able to delineate the various sectors of their unconscious to help them to see what they are asking of us, and what their internal world of bad objects hold over their souls. We might say at moments like these that are repeated over and over again, across a great span of time, that the patient is asking us to renounce our role of “therapist” and take on the role of Therapon.

Wilfred Bion (1970) says that the therapist must be able to “suffer” what the patient is tortured by in order to establish credibility with them. He says we must be able to enter into an at-one-ment (atonement) with them in order to offer them the evidence that they are not locked away in the past position of abandonment or withdrawal being lived out in the transference. As with all such states of identification, they are transitory. Eventually they must be aided to see they are not the monsters they fear nor the angels they dream of. Neither love nor hate will ever produce the desired outcome of integration, acceptance and most importantly, the mourning of the impossible dream lurking at the core of the self.

Our attention and attunement is to be directed toward the internal conflicts that are at the core of the patient’s problems and become projected on to and into the therapeutic relationship. We can offer help that might assist them in solving their problem but we must not climb upon the sacrificial altar in their place. Such sacrifice might meet the therapist’s unprocessed needs but does not lead the patient forward to be able to realize the complexity of their circumstances and the requirements necessary to achieve a productive separation and creative independence.

Notes.

Bion, W. (1970), Attention and Interpretation. London, Karnac, 1984.

Freud, S. (1923), The ego and the id. Std. Edition, Vol 19. , 48-59.

Klein, M. (1935) A Contribution to the Psychogenesis of Manic-Depressive States. Int.J. Psycho-Anal, 16.

Racker, H. (1968), Transference and Countertransference. IUP, Madison, CT.

Michael Parsons and the Logic of Play in Psychoanalysis

By Yeshim Oz, MS, LMHP 2nd Year Student Core Program

As we come nearer to the IPI weekend in January, I became curious about the guest speaker, Michael Parsons. In the age of technology, it was not difficult at all to come across tens of articles written by him by just one click. (Ok, that is a bit of an exaggeration; you have to enter your username and password to use the fabulous Pep-Web). Since I am a child therapist and play is part of my life, one of his articles, although not a recent one stood out for me: The Logic of Play in Psychoanalysis (1999).

Although there is nothing extra-ordinary about the use of play in child psychotherapy, the idea of play in adult psychoanalysis might seem a little peculiar at first. However, in his article, Parsons demonstrates beautifully how play, with its paradoxical nature, is ever-present in psychoanalysis. “The paradoxical reality” he says, is “where things may be real and not real at the same time”. Isn’t it the essence of transference? When the patient experiences the analyst as the father or mother, it is true in the sense that the patient experiences it, but it is also an illusion. As Parsons reminds us, Klauber suggested that the therapeutic value of transference does not depend on resolving the illusion but on accepting its paradoxicality. This acceptance opens up a space for the therapeutic couple to do the analytic work without undermining the experience of the patient as a mere illusion. Where is the play element in here? Parsons says, ” the play element functions continuously to sustain this paradoxical reality”. The “as if” quality of play enables the patient -and the analyst as well- to think, imagine, and play with possibilities.

Parsons continues to explain the intricate connections between play, playfulness, humor and irony and stresses the spontaneity and the importance of the analytic frame. He gives excellent examples from clinical material that show how each of these aspects emerges spontaneously from the interplay between the patient and the analyst that would deepen the analytic process.

With all its seriousness, the article evokes in the reader a sense of playfulness, which might have been long forgotten, especially for those who work with adults. As far as I am concerned, it gave me a new understanding when thinking of my young clients who often express, silently or quite loudly, how magical the therapy room (a play framework- in other words) feels to them and to me at times. I am certainly more excited now than before for the January IPI weekend with the anticipation of a playful, humorous, yet serious work.

IPI Gala Award Dinner and Dance

IPI Hosts Gala Awards Dinner and Dance

| The first International Psychotherapy Institute (IPI) Gala Awards Dinner and Dance took place on Saturday October 22, 2011 at Kenwood Country Club in Bethesda, Maryland. The guest of honor was Jason Aronson MD, Premier Publisher of psychotherapy books and Co-Founder, IPI, and inaugural recipient of the David and Jill Scharff Award for contributions to mental health. The dinner was held in Dr. Aronson’s honor and in appreciation of founding board and faculty members 1994-1996. The event was organized by Gala Chair Sheri Rosenfeld and her committee Joanna Bienko, Anabella Brostella, Karen Greenberg, Jill Scharff, andLea de Setton. |

| Sheri Rosenfeld, IPI Board Development Chair welcomed the guests to the IPI benefit and handed over to Michael Stadter, IPI Founding Faculty and Board Vice-Chair, as Master of Ceremonies. |

| Michael introduced faculty to describe IPI’s community involvement. Caroline Sehon (Chair, IPI Metro Washington) spoke about the videoconference teaching program for therapists in remote areas. Colleen Sandor (Co-Chair, IPI Salt Lake) attested to the value of IPI’s affiliation with Westminster College. Carl Bagnini (Co-Chair, IPI Long Island site) his work with Latino fathers. Lastly Vali Maduro (Chair, IPI Panama) and Anabella Brostella (Chair, Foundation for Healthy Relationships at IPI Panama) showed IPI-Panama’s film of work with Operation Smile plastic surgery programs to correct children’s congenital deformity, suicide prevention efforts, and programs for teenage mothers. |

|

Books by IPI authors were on display for guests to browse. |  |

| After dinner, in a short program to honor and thank colleagues and supporters, Geoffrey Anderson IPI Director, recognized the contributions of founding faculty 1994-1996. Pictured, from left, are Founding Faculty members Carl Bagnini, Yolanda de Varela, Charles Ashbach, Walton Ehrhardt, Sharon Dennett, Judith Rovner, Lea de Setton, Mike Stadter, and Michael Kaufman. (Not present: Kent Ravenscroft and Paula Swaner) |

| Chris Hill, Treasurer, IPI recognized the Founding and Inaugurating Board of IPI (then IIORT) 1994-1995. Pictured are Kent Morrison, David Scharff (Founding Co-Director), Jill Scharff (Founding Co-Director) Jason Aronson (Founding Board Member, NYC). (Not pictured are Dennis Blumer, Yvonne Burne, Dickson Carroll, and Lorna Goodman.) |

| Michael Stadter, Board Vice-Chair, IPI announced the inauguration of the David and Jill Scharff Award. Drs. David and Jill Scharff are co-founders of the International Psychotherapy Institute. They teach and supervise at IPI and IIPT and practice psychoanalysis and psychotherapy with children and adults, couples and families in Chevy Chase. They spearhead IPI’s international outreach, our message carried in translations of their many books on psychoanalysis and psychotherapy in German, Italian, Chinese, Korean, and Russian. |

| David Scharff, Co-founder, Board Chair, IPI and Jill Scharff, Co-founder, IPI introduced the recipient of the award. Dr. Jason Aronson, a physician and psychoanalyst, founded and directed for over 35 years Jason Aronson Inc., the premier publishing company of highly regarded, professional, scholarly books by respected and gifted authors in the field of psychotherapy until 2003, when Jason Aronson became an imprint of Rowman and Littlefield. In 1994, Dr. Aronson joined David and Jill Scharff as the third co-founder of IIORT, now called IPI, and has been a good friend to IPI ever since. Dr. Aronson was the founder and editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Psychiatry. He resides in New York City with his wife Alice Kaplan. His daughter Jane and her family live in California. |

| A delighted audience rose to its feet in thanks and expressed its exuberance on the dance floor thereafter. | ||

|

|

|

The Gala was a terrific success, both in terms of attracting support and in giving all our guests an enjoyable, entertaining evening. Donations of table décor from Jonathan Willen, graphic design from Leanne Poteet, photography by Darin Del Rosario, and plant materials from American Plant Food were gratefully received. With their help and the generosity of our guests, IPI raised $22,000 to support outreach programs.

Acknowledgements

Helpers ($150-499)

Sharon Alperovitz

Dorothy and Larry Arnsten, Arnsten Foundation, in honor of Jason Aronson

Nancy and Richard Bakalar

Lawrence Birnbach, in honor of Jason Aronson

Jim and Elise Blair

Norma Caruso

Maria Checa-Rosen

Meg and Jim Cooper

Steven, Susan and Malka Drucker, in honor of Jason Aronson

Walt and Carol Ehrhardt

Bonnie Eisenberg, in honor of the Founding Faculty

Randy Freeman

Cleo and Michael Gewirz

Jeffrey Glindmeyer

Linda Hopkins

Michael Kaufman and Maria Ross

Chris Keats

Steven and Susan Levine

Jaedene and Chuck Levy

Doris and Scott Mattingly

Kent and Dale Morrison

Michelle Pfeifer

Mary Jo Pisano

Susan Plaeger

Eleanor Rosenfeld

Helen and Paul Schmitz

Eleanor and Arthur Siegel

Suzanne St. John, in honor of Charles Ashbach

Stan and Hilary Tsigounis

Wendy S. Wall, in honor of Jill and David Scharff

Kim and Judy White

Tappy and Robin Wilder

Friends ($500-$999)

Dennis and Tansy Blumer

Henri and Rachel Parens, in honor of Jason Aronson

Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Rumford

Supporters ($1000-$1499)

Lea Setton

Harold and Nancy Zirkin

Sponsors ($1500-$2999)

Jason Aronson and Alice Kaplan

James Finkelstein and Laurie Ferreri

Sheila and Chris Hill

Hugh Hill and Sandra Read

Anna Innes and Charles Carter

Chuck Muckenfuss and Angela Lancaster

Michael Stadter and Jane Prelinger

Director’s Circle ($3000-$3499)

Jill and David Scharff

Angels ($3500 and above)

Sheri and Rob Rosenfeld

Caroline Sehon

Group Narcissism and the Penn State Situation

Carl Bagnini, LCSW, BCD

In reading the reports and investigative results regarding ongoing and extensive child sexual abuse at Penn State it occurred to me that what happened at the institution can be viewed as a covert narcissistic male sub-culture of collusion, power dominance, and ruthless self-indulgence. The overt behavior against children was denied, justified, and covered up for years, by a good old boys club, reeking of mutual stroking. In maintaining the huge money maker, Penn State football, and coach Paterno’s god-like reputation the “group” rationalized hatred and envy of young children, by reducing them to objects of lust and control.

The fear of exposure of the abuse has a history. The facts were known. The house of cards from top to bottom was maintained due to the narcissistic motives of the men in the positions of power and influence. The homo-affiliative nature of sports, especially “contact” sports like football fosters in older males insecurity and repressed envy of the young. The young have a long life ahead, while the elders fear death and facing the questions of how good a life has one lived? Inflated self-importance is rampant among ageing men who see young and virile athletes as reminders of time passing, and lost physical prowess. Mentally and emotionally these fears create a veil of secrecy, and denial, and in Sandusky’s case, the full blown acting out of a malignant narcissistic pedophile. What type of environment could rationalize or deny abuse was taking place in a public space? We did not abuse the children, only he did? A flimsy excuse to any thinking individual, and the cover up was deep and wide. There had to be, in addition to administrative bottom line motives (Penn State economics) to cover up the influence of a group “culture” that avoided the personal pain and suffering involved by “knowing” what was occurring. Why the lack of conscience? Was Sandusky so beloved he could weave a Svengali web of innocence? It is too simplistic an assumption that one person relied totally on charisma and the scam of “devotion to improving the lives of children”. How could one man continue getting away with criminal behavior inside a locker room shower while others knew?

Narcissism in groups is well established; the worst example is Nazi Germany where people including victims followed orders and perpetrators later insisted they did not know the extent of the planned extermination of millions of countrymen, women and children. We are all subject to the narcissist’s seductive smile. We long to bask in his acceptance since it can be so intense because it is so fleeting. Sandusky, Paterno and others in power and in lower positions had to be caught up in denial by idealizing the institution—the god-like Football program, Penn State and the cold hearted credo we are “too big to fail” (remember Wall Street and the big banks?).

But beneath the now obvious institutional loyalties we must admit to a malignant negation that played its more sinister unconscious part: the hatred of the children’s vulnerabilities, that as victims they threatened the established belief system and its denied truths. In a caring world victims have justice, and by denying them protection and a voice the group ensured it was faultless, or justified. The victim is hated, not the victimizers. They are the scapegoats. That is group negation at its worst because any heinous crime can be rationalized.

Narcissism and the hatred of children exist in our society. When we hurt children with impunity or bear witness to acts of cruelty and are indifferent, or when we turn away from large scale cuttings of services to children and families, we are all responsible; but only if we remain silent as individuals or in groups can insidious forms of abuse, such as at Penn State go on institutionally—the end of a humane civilization is determined by the quality of care of our children and the elderly. We need to remember the old Pogo cartoon with its sage warning: “We have met the enemy and the enemy is us”.

Changes in Brain Activity After Analytic Treatment

The following article link was sent to us by Dr. Horst Kaechele. Dr. Kaechele was our distinguished guest presenter at our October 2011 Weekend Conference. Dr. Kaechele is a German psychoanalyst and researcher. His work has done much to demonstrate the usefulness of psychoanalytic treatments when other groups have been claiming there is no research basis for analytic work. This current article is on changes in brain activity in depressed patients after analytic treatment.

Kent Ravenscroft, Founding IPI Faculty Member, Wins Bruno Lima Award

Kent Ravenscroft, author of Haiti Fair Well, and Emeritus faculty of IPI, was selected by the Committee on Psychiatric Dimensions of Disasters of the American Psychiatric Association to receive the 2012 Bruno Lima Award for his volunteer work in training mental health workers in Haiti after the earthquake. The Bruno Lima Award recognizes outstanding contributions of APA District Branch members to the care and understanding of the victims of disasters. Contributions include designing disaster response plans, providing direct service delivery in time of disaster, or in disaster consultation, education, and/or research. IPI members may remember seeing in this blog prepublication drafts from Kent’s diary of his time in Haiti. IPI congratulates Kent on his achievement.

Volunteering in Bosnia September 2011, Part 4

By Sheri Rosenfeld, LICSW, LCSW-C

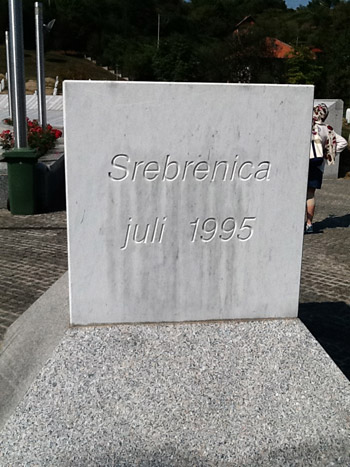

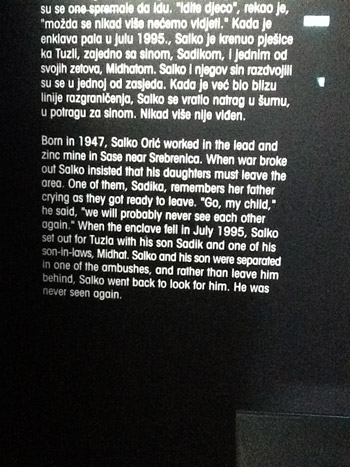

Day 6: Srebrenica

Of all the days in this journey, this 12-hour period of time on the last day was the most memorable, disturbing, life changing, and eye opening. Our day began with a 3-hour treacherous drive through the beautiful mountain sides of Bosnia. Our goal was to reach Srebrenica in order to pay homage and bear witness to one of the world’s greatest post World War II tragedies. Although many tragedies in Rwanda, South Sudan, the World Trade Center, Afghanistan are horrendous, I know of nothing in contemporary world culture as diabolical as the atrocity on July 11-13, 1995 in Srebrenica, a small village 10 kilometers from the Serbian border.

The background, brief story, is that the Serbian leader wanted to seek revenge on the Bosnian Muslim people for invasion by the Turks in the 1400s. But most, if not all, Bosnian Muslim people do not see identify themselves as Turks: They are Slavic people. Even though they may have ethnicity in common with the people of the Turkish Empire, many do not identify them, and have not been able to comprehend the logic of the revenge motive that led the Serbs to want to annihilate them. The Serbs surrounded the city of Sarajevo, by shutting off all access to food and water and electricity for 48 months. The war, however lasted 5 years in the villages, Mostar, Zenica, Serbenica. The great world powers did not come to their aid until the Dutch sent in a UN Security team, but only to keep peace, not to fight. The Dutch intervention proved to be the catalyst for the massacre of 8,000 men and boys and the desecration of the women by torture and rape since their orders were to protect without firing. That proved to be worthless.

On the command of the Serbian leader, a whole population of innocent people was exterminated in a matter of a few days, and the country was left traumatized and beaten. Twenty-five thousand people fled to a small village, Srebrenica, a protected UN Military safe zone, where they were supposed to be safe. What happened then was remarkable, horrific, and difficult to digest. One woman told a story of how her baby was crying in her arms because they hadn’t eaten for days as they walked to this village. A Serbian soldier told her that he knew how to quiet the child, and slashed his throat in the mother’s arms. Thousands of young boys 12 and up were separated from their mothers and collected with their fathers to be executed. The mothers and daughters were taken on a bus and transported to other buildings having no idea what would become of their sons and husbands. In that day, 8,000 men and boys were executed and buried in mass graves which were later moved so as not to be found. All the while, the people in Sarajevo could not help because they had no idea that this was happening. Much of the guilt, I am told, stems from the fact that they could not help their neighbors and fellow Bosnians.

After we visited the burial grounds (see below) and the museum and listened to a documentary about this ethnic cleansing, we visited a woman’s home. Jasenka, had a beautiful greenhouse, a wonderfully clean home, many pastries and Turkish coffee to share with us. She then told her story of how she was separated from her son and husband as she was fleeing to the old factory where everyone believed that the Dutch soldiers would protect them. 25,000 people came to that factory. Women and children were separated from their sons over 12 years of age and all the men. But her story, even though very sad, is also a story about hope and determination and pride. It’s also a story about the possibilities in life when you connect with others to gain strength.

Jasenka lives alone now. But she has a daughter who witnessed the atrocities along with her on that day. Her daughter was determined to not let her life story or the loss of her family derail her. She went on to get her Masters degree and PhD and now lives in London with her husband and 2 children. Jasenka created a beautiful garden. She grows all the food she needs to survive and also has a cutting flower garden. She now has a small souvenir store that sells flowers across from the memorial park where her son and husband are buried. Not only is she doing well in business but she feels she is healing just by being near her family. She belongs to the association where the women support each other in their various businesses, all of them learning through Women for Women that they can use their talents in commerce.

What is most remarkable about these women is that they used to follow their husband’s lead. They had no idea of what their rights were or how to make an income, and they did not even believe they had a voice. Many of these women do not have an education past elementary school, cannot read or write. But through WFW they have an organization that believes in them and gives them a future.

Bosnia has very few opportunities and the world still seems to have forgotten that these people are hurting terribly. I was grateful to be a witness to their history, their struggle, and their resilience. I hold them in my mind and in my heart, and I hope to return one day and bring others with me.

Volunteering in Bosnia, September 2011, Part 3

by Sheri Rosenfeld, LICSW, LCSW-C

Day 3: Zenica

I want to start with this picture:

In the morning we were driven to the WFW headquarters where we learned more about the war and what led to it, what it was like for the Bosnian Muslim population, and which tools of terror were used against the people of Sarajevo and beyond. Women have always been used as a way to exhaust and ruin a society. If you rape a woman over and over, she feels torn inside and out, and cannot keep her family alive and hopeful. So the Serbs, in this case, went into a part of town Grabvci and raped 95% of the women, old and young, repeatedly. These women live with the scars of that violence in addition to the loss of their husbands and sons.

I met this woman, Edina, when I purchased some of her knitting:

She is the only person in her family who works. Ninety percent of all the women who come to WFW are illiterate. But the translator explained to her that I would buy her crafts so that I could give presents to my family, and asked her if she would tell me her story. When she hugged me, she felt no different to me than my own grandmother. These people were targeted because the Serbian politicians wanted the Muslims out of Bosnia even though the Muslims are in the majority. It is unfathomable. The people now live with psychological disorders, malaise, depression, economic depression, and hopelessness. They appear dazed. I think that it contributes to the lethargy in the work place. The reason everyone is out enjoying their smoking (everywhere) and their Turkish coffee is because no one has a job!

The picture below is the beginning of our entry into the underground tunnel:

(Pic 9). The people of Sarajevo were cut off from medicine, electricity and water. They were prisoners in their own city. When they tried to flee and get to the airport they came under sniper fire, even while the UN Peace Keepers were here. You can see on their faces, as they describe this horrible experience, how betrayed they feel by the Dutch Peace keepers who didn’t stop the Serbs from killing them. So they built a 700 meter tunnel in order to escape and to bring supplies into town from the airport.

This is the famous market place that is about 4 blocks from my hotel in Sarajevo:

A grenade hit this marketplace in the middle of a busy day and killed over 80 innocent people. The city has markers on the ground to demark where people were killed. The government made a commitment to paint these markers red but they have not done it. But people can see them anyway.

So far what I am beginning to take away from this experience, something I have always known, but now feel acutely, is how wasteful ignorance and prejudice are, and how terribly destructive they can be. These people are not different from us. They have the same dreams, love their children, enjoy a good coffee, and want to have fun.

Day 5: Zenica

Yesterday we were taken to the home of a couple near a rural area called Zenica:

We were told that the woman, Rosena, is a graduate of the Women for Women program — which essentially means that she spent a year going to class on women’s rights, independence, financial independence, learning a trade, or running a business. Many women can open a business when they have learned to pick medicinal herbs, knit, crochet, make jewelry and crafts, cook, farm, and sell their wares. They are taught how to be an entrepreneur and what it takes to be a leader. They are taught the importance of unifying other women to support them and create networks. These women, not fighting in the front lines as did their husbands and sons, managed to keep their families alive. They made grass soup when the entrance to the city was under siege, under constant barrage from grenades and shelling and sniper attacks, and there was no water or food or medicine. When their families were dislocated and removed from their surroundings, they had to leave their prized possessions behind and find shelter somewhere else, never to return to their homes now occupied by Serbs or other families. One girl fled so many times that all she was left with 5 years later was one suitcase of her possessions. Everything else was gone and never found again. All semblance of life as they knew it was over.

Nonetheless, Rosema, the woman in the picture had written in her graduation speech, from the year long WFW program, that it was at the point at which she felt she had nothing left to live for, she found WFW. Her husband had gone to fight at the front lines and she had had no idea if she would see him again. He was everything to her, as were her 3 sons. She was at a loss. But when she found support at WFW she gained belief in herself and her future.

We entered Rasema’s very modest house, a beautifully clean and lovely home. The table was filled with homemade treats that she prepared — Turkish pies, fruit, a homemade beet and carrot juice, desserts, Turkish coffee, cheese, tomatoes, and fruit. I knew that this woman had great pride in herself and her family. She looked at each one of us very warmly but carefully. And then she began to tell her story. Midway through her description of life during the war, she broke down saying, “Never again”. And we were silent. I looked at her and cried. She came over to me, kissed me, and said, “You are my sunshine!” I was amazed. Here I was coming to comfort her, and she was comforting me! And then her husband walked in. He listened to the story she was telling about how hungry they had been, how she would look at a bag of plaster and fantasize that it was flour. And then he cried. Her husband could not find work because the factories closed and there are no jobs, or to get one he might have to bribe an official. It had been 16 years, and they were still distressed by their story.

But Rasema had become resourceful. She began to farm. She now has a greenhouse for growing vegetables. With her earnings she is buying another greenhouse and is now selling her vegetables to the markets. She will acquire another greenhouse because she realizes roses will sell for even more. Her husband still cannot find work but he provides tremendous support as do her boys, and now he works for her. She feels blessed and in control and has her own business. She is a strong woman now.

What I have realized is that when people are in crisis they must move into action. Action is motivating, gives the mind a purpose and the reassurance of doing something to combat the problem. It’s the aftermath, the lethargy, the hopelessness, the fear that life won’t get better even though you are working, the inaction — that’s what kills. That’s where support, education, inspiration, and of course, resilience come in.

I didn’t want to leave Rasema that day. I knew I may not see her again. I also knew that she represents something I so admire in people: resilience, strength, and a warm heart. She has all three, and I was honored to be in her presence.

Volunteering in Bosnia, September 2011, Part 2

by Sheri Rosenfeld, LICSW, LCSW-C

Day 2: Sarajevo, evening

Tonight our whole group finally came together with the six Bosnian heads of the WFW organization. My preconceived notion of the Muslim Bosnian women was immediately challenged as I sat next to women who appear to be Muslim by affiliation but who are secular, blond and blue eyed We began the evening watching a film about a Bosnian mother and daughter. That was difficult to watch but nothing compared to what was coming. Saieda, the head of the Bosnian WFW, told her story of how her family survived and how she and her sister lived in an apartment on the front lines and had to dodge the snipers’ bullets as she walked down her stairs. I saw the sadness and tears in the Serbian women’s eyes as they sat with the Bosnian Muslin women. My understanding, from the others I spoke to, was that the guilt that the innocent Serbian people feel is overwhelming. Many fled Bosnia just to protect their sons from mandatory army recruitment. Many feel that their hands were tied as they watched their neighbors, women, children, and men, all die senselessly. This film was a painful reminder.

As the evening progressed, women shared their stories in a more tempered way, I was that their stories will unfold as we move on. What I was left feeling at the end of our evening was a concern for the staff members of WFW. Listening on a daily basis to hundreds of survivor stories of rape and execution has the potential to create secondary trauma. But the women with WFW have their own nightmares of hunger, loss, death, massacres, and brutality. I wondered, how might they protect themselves from continuous emotional injury.

Day 3: Sarajevo, dinner

There are many times when I have been privileged to bear witness to someone’s life-story. I feel honored to be entrusted with something so delicate and so personal. But tonight I hear stories I will never forget. The phrase “Never Forget” is familiar to me as a Jewish person, and it echoes in the Bosnian Muslim population. The Bosnians will never forget as much as they wish they could. Nonetheless, keeping their story ongoing and fresh is critical so that, perhaps, history will not repeat itself. That’s hard to believe but it’s a strong wish.

Tonight I sat next to two Bosnian women who work at WFW. The first woman, Ajla (EYE-LA), is a 25 year-old with long, light brown hair and beautiful doe eyes. She is bright and full of a calm energy. By her name she seems to be Muslim but her father was an Atheist and her mother an Agnostic. She is fully educated, speaks 5 languages, and works as an interpreter for WFW. The second woman, I call Farida, has been a substantial participant in WFW. In 15 years at the front lines with all the women, she has endured and contained the horror and tragedy of their stories. Farida says that whenever she felt tired and in doubt she just thought of the women who needed her, and she was energized.

Ajla tells her story from the eyes of a child. She was 5 1/2 years old when the war broke out. Her parents did everything they could to protect her from the war and the hardship, but they lived on the front lines and heard bombing all the time. Sometimes Ajla would walk outside and see the flames burning from the buildings. She said that her father, than 40 years old, went to fight. He chose to do that rather than flee. She said that even though he saw so many people destroyed and felt that there was no use to the war, and suffered a debilitating injury, he would choose to do it again rather than flee. He said that he felt someone had to fight for his children and grandchildren.

Ajla describes to me the horror of the day that her father took her to the main library, which had already had been destroyed by fire once in a war fought many, many years ago. He loved books and was a well read man. Although he never said a bad word about the Serbs, she says, he wanted her to know that what they were doing was not just destroying people’s lives but their history, culture, education, and knowledge. That he felt was a true tragedy. She remembers the flames and the ashes of paper filtering down in front of her face. She remembers sleeping in her little boots and coat, always expecting that they would have to run out of the house quickly. She feels she cannot help but feel bitterness and sorrow. Mostly, she says, she can’t understand why anyone would want her dead.

Farida was in her late 40’s early 50’s — beautifully dressed, magnificent face, but with sad and watery eyes. She spoke only Bosnian, and so I heard her story through an interpreter. I could tell that she was a passionate woman. When I asked her what her experience of the war was like she said, “If I could forget I would, but I can’t. No one should have to go through that.” Farida has no children, and so her husband is everything to her. He is her whole life. When he went off to fight, she felt that her whole world would collapse. She remembers burning her shoes in the fireplace for warmth. She tells of how she had to become creative with recipes, making grass soup, or cabbage rolls from plants that looked like cabbage leaves. She remembers standing outside her front door, and suddenly a sniper shot a little girl while she was running with her friends. Then she said, “That is why I listen to the women’s stories. Someone has to.”