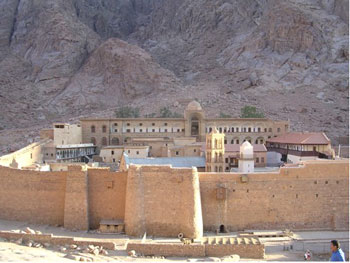

In my previous posting, I described a remarkable trip that I took a year ago to the Middle East in the company of Christian seminarians of various denominations. The trip stimulated many personal reflections on faith and prejudice and I wrote about some of them. In this blog, I look at the role of faith and prejudice in the formation and maintenance of personal identity.

I will start with the premise that identity is partly defined by 2 perspectives of others. First, identity is defined by who we love and feel are part of our group (family, religion, country, etc.) – THIS IS ME. Second, it’s defined by who we see as different from us and who we might fear or hate – THIS IS NOT ME, REALLY NOT ME. If our view of these not-me people changes, it may dramatically change the way we see ourselves. We see ourselves both from the standpoint of who we are and who we are not.

Let me give a simple hypothetical example. Let’s say I’m prejudiced toward Arab Muslims. I’d maybe see myself and Americans as generally good, Christian, responsible peace-loving people. I’d see Arab Muslims as, perhaps, bad, violent, untrustworthy infidels. But, what if my view of Arab Muslims changes into one that is more positive, nuanced and accurate? Then my view of myself and America may be less self-righteous and positive and I would need to confront more of the negative aspects (e.g., violence, untrustworthiness) in me and in the groups that I affiliate with. That can be very uncomfortable and a powerful force for holding onto prejudice. If my view of my enemy changes, my view of myself changes. (I’ll leave to the reader how this might apply to conflicts between Republicans and Democrats in this election season.)

Here’s a real example. In an NPR interview in 2005, Eyad El-Sarraj, a psychiatrist and President of the Board of the Gaza Community Mental Health Programme, spoke about the effects of the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza on Palestinians. He noted that, while this was a very positive move, it created an identity crisis for them. Now Palestinians would have to shift away from defining themselves through their opposition to the Israeli occupation. The shift would need to be toward coping with the differences among themselves – “Who am I if I do not have my enemy?” Last summer we saw that, tragically, Palestinians in Gaza dealt with it in one way through the definition of enemy being other Palestinians – the Fatah/Hamas civil war.

RELIGIOUS IDENTITY AND PREJUDICE

For all of the enormous benefits of faith, religious identity can and often does lead to prejudice. Of course, this isn’t inevitable but I do think there is serious potential danger here. Consider only a few of the terms used for members of various faiths:

The Chosen People

The Eternal People

The Children of God

The Faithful

The Elect

The Believers

Christian Soldiers

Defenders of the Faith

Saints

So, if “we” are the chosen, who are “they”? Here’s what I worry about. Language structures our experience. When “we” refer to ourselves with such terms, it can unconsciously structure our experience of others as not only different from “us” but as not being as good as “us.” I think it can lead to a type of arrogance rather than to a sense of humility. If “we” are that list above, then what does that make “them”? Here are some possibilities:

The Chosen People — (The Not Chosen Ones)

The Eternal People — (The Mortal People)

The Children of God — (The Children of Who?)

The Faithful — (The Unfaithful)

The Elect — (The Rejected)

The Believers — (The Nonbelievers)

Christian Soldiers — (The Infidels, Pagans)

Defenders of the Faith — (Enemies of the Faith)

Saints — (Sinners)

At the extreme, this potential for seeing “us” as good and “them” as not good can transform into “them” as downright bad or evil and worthy of being cleansed, conquered or killed. Here we see how violence and war can be initiated in the name of God.

One of the most outstanding benefits of religious faith is that, in many ways, it can transform the unbearable into the bearable. Perhaps the most unbearable and terrifying experience of human existence is death and the knowledge of it: I will die, everyone I love will die, everyone dies. Religion can make death bearable through faith in God, in salvation, and in the afterlife. From that standpoint alone, the potential for faith to be used (I would say misused or perversely used) to do violence to others is great – the person who kills the enemy will be saved for eternity. In my previous posting, I gave 2 of the many possible quotes by religious leaders throughout history invoking killing of others that will lead to salvation in an afterlife. I’ll repeat them below:

“Now we hope that none of you will be slain but we wish you to know that the Kingdom of Heaven will be given as a reward to those who shall be killed in this war [against Muslims].” (Pope Leo IV, 9th century CE)

“The martyr [referring to suicide bombers], if he meets Allah, is forgiven his first drop of blood; he’s saved from the grave’s confines; he sees his seat in heaven; he’s saved from judgment day; he’s given seventy-two dark-eyed women; he’s an advocate for seventy members of his family.” (Sheikh Isma’il al-Adwan, 2001 CE)

This extreme of violence toward the different other has its beginning with our fear or intolerance of differences in others – our human predisposition to prejudice. It can be frighteningly catastrophic when the power of religion is attached to it.

IN CLOSING

I’d like to share 2 quotes that are very different from the previous 2. They speak of the struggle toward human connection and against divisiveness — even in the face of violence and trauma. Both are from Henri Parens, a psychoanalyst and Holocaust survivor, who has written extensively on aggression and prejudice. He was also a speaker at the IPI prejudice conference in Salt Lake City and is a co-editor of the book from that conference: The Future of Prejudice: Psychoanalysis and the Prevention of Prejudice (2007).

Parens described the experience of Rami Elhanan, an Israeli whose 14 year old daughter was killed in a suicide bombing in 2005 and whose initial reactions were rage and revenge.

“Then Elhanan met Yitzhak Frankenthal, whose own son had been kidnapped and killed by Hamas. Frankenthal, a founder of Parents Circle — an organization established in 1995 for the purpose of bringing together to meet and to talk Israeli and Palestinian parents who had lost a child to these reciprocal killings — talked Elhanan into attending one of their meetings. Elhanan was profoundly moved on hearing Palestinian mothers express the same grief and rage that he felt; his rage and wish for revenge turned into wanting to foster dialogue among bereft Palestinian and Israeli parents. While on both sides of the conflict there are some who think the Parents Circle is a crazy idea, others – seeing the dire state of life revenge has wrought, and is sure to continue doing, so long as it is the solution deemed most honorable and worthy – assert that we have to see each other as we are, not as we distort each other to be, and that we have to talk together in order to live together.”

Who is “us” and who is “them”?

Parens, wrote the following about the Holocaust and prejudice:

“We must not let it happen to us again.

We must not make it happen to others.

We must not be victims, and

We must not be perpetrators.

We must learn

To live together

With our difference.”